2. Rituals of Beginning

My head feels foggy and my whole body feels tired. I am vaguely hungry, and I debate whether eating something will make me more energized. I don’t want to take the time to cook something. I don’t remember feeling this tired a few minutes ago, but now that I’ve sat down in front of my computer, thinking feels like trying to do math problems without my glasses on. I debate a nap. I open my planner and start looking at the week. I have three other times bookmarked for writing this week, but I can’t push today’s task to any of those times without starting a domino effect of delayed tasks. I could potentially do two shorter writing sessions before work the next two days. Would that be enough to get something done? Sometimes shorter sessions work well, but it means getting up earlier so I need to go to bed on time. I consider whether there are obvious obstacles to going to bed on time tonight. Am I just kicking the can down the road? What if I can’t focus any better in the morning? This is the problem — I’m always thinking I’m going to be more able to write later, and most of the time it’s not true. This is probably, cumulatively, the reason I’m not where I’d like to be in my career. A really focused and motivated person would write today and in the morning. If you add up, end to end, all the times I’ve put off writing for another day, that’s certainly multiple plays I haven’t written. And see? That thought makes me so stressed out that I can’t possibly focus. Any amount I could write today feels like peanuts. A truly disciplined and motivated person would set these concerns aside, and in a fit of determination, they would crank something out right now. I’m clearly not that person. And I think it’s because I’m not sure it really matters. Even if I did manage to write something good, and get it produced, what does that really do? It’s not like my work is ever going to reach that many people. You have to get awards to get the kind of momentum where you start to reach more people, and I haven’t gotten very many awards. Maybe, if the next play I write were to win an award or get produced in New York and get a little attention, then I could get some momentum. But when you get momentum you have to be ready to capitalize on it, which ideally means you need to have another play ready to go. Or at least an idea that’s still messy but fairly fleshed out, in that kind of messy but catchy stage that people find attractive. And even if that happened, this is still all about my own selfish little successes. Even if I were to manage to do all those things, what good would that actually do anyone? If I’m going to put this much agonizing and this much life energy into something, should it really be this thing that doesn’t materially improve anyone’s life, or alleviate any suffering, or——

I am twenty minutes into this argument with myself when I realize I could just not be having the argument.

It’s like when you realize you’ve been on the phone with a robot, not a real person, and that whatever you say, they’re just gonna keep going. Oh, you realize, I’ve gotten this call before. I recognize this script. And there is no end. I can’t redirect or resolve the conversation. The only thing there is to do is hang up.

The problem is, I agree with much of what the robot is saying. I want these issues resolved. I want a nap, and I want to believe in the value of American theatre, or perhaps abandon it, or at least become better at——

And there I am, back on the phone.

I have really only one strategy that works when I find myself on the phone with the robot. And that is to tell myself: lower your standards. You do have to write, and you have to write now. But you can do it badly. In fact, that is the task: write the bad version, the absolute clunkiest, stupidest, lamest version you can imagine. That’s the task, and if you do that, then you have succeeded. If you do that, you can be done for the day. And you can worry about the rest tomorrow.

Okay… I say, not hanging up, but setting the phone down, so the robot’s voice is fainter. If you’re sure. (Sneakily, I think, maybe I will think it’s going to be bad but actually it will turn out to be good! Maybe it will actually be the best thing I’ve ever—) NO. I look myself sternly in the eye, take myself sternly by the shoulder. Listen, I say, I don’t want to hear any more of that nonsense. You’re going to forget about being good. Being good is useless, and irrelevant, and of no use to you. You’re just going to write down your little words, and they’re going to be bad, and that’s going to be that. Are we clear?

Okay, I say to myself, fine. It’s a deal.

Once I agree to write badly, I can begin.

New Years is my favorite holiday. I like its mix of earnest self-reflection and rowdy champagne drinking. And despite the fact that I grew up with less traditions around new years than most other holidays, it was always the holiday that seemed to hold the most potential for meaning to me. I liked all the activities we did for Christmas and Easter and Fourth of July and Thanksgiving, but being raised by non-Christians with a healthy dose of skepticism about America’s founding myths, all these holidays added up to fun traditions our family did in *spite* of the day’s larger meaning, not because of it. In my late 20s, I started a new years tradition with a few close friends, and we’ve kept it up for nearly a decade now. There has been some trial and error in our homemade rituals, the question being, how do you make a good beginning?

The practice of not just marking but celebrating the start of a new year is, if not universal, notably widespread across geographies and cultures. The first recorded new years celebration was roughly 4,000 years ago. There isn’t a consensus on when you should fix the seam in the circle of the seasons — you can find new years celebrations in every season of the year. (Next up is Lunar New Year of course, in February, followed by Nowruz — Persian New Year — in March, then Songkran — Thai New Year — in April. Summer brings Islamic New Year in July. Autumn includes Rosh Hashanah in September and Diwali in November…) What does seem to be shared is that we’d rather not just keep going round and round, with no end in sight, and that we’d prefer the reset to be more than clerical. That there’s something nice about the chance to take stock, draw a line in the sand, and begin again.

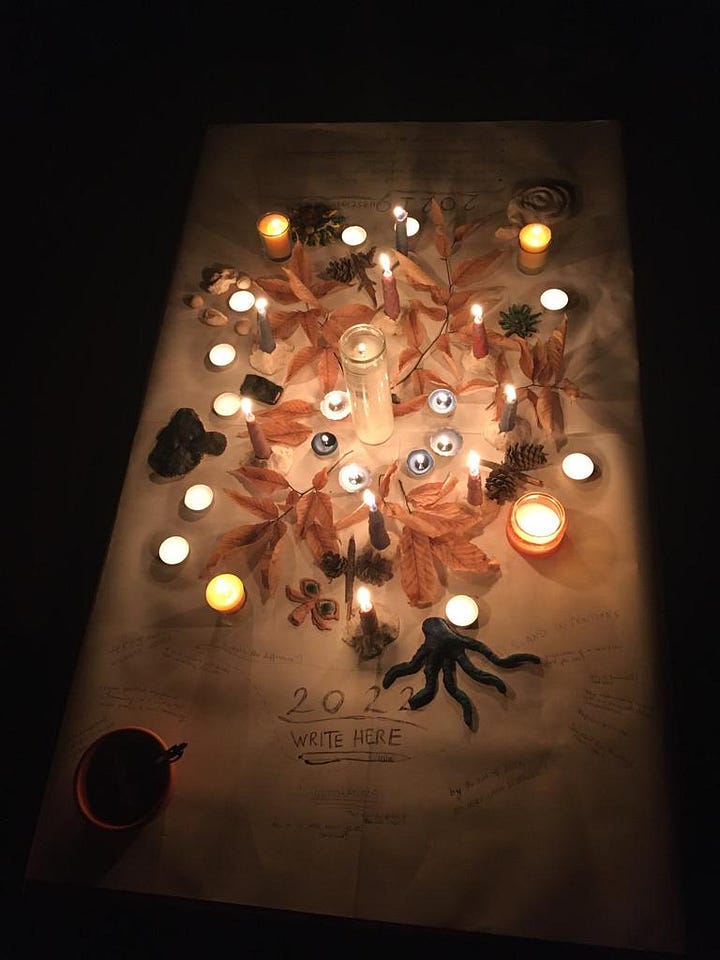

The hour or two leading up to midnight at my new years gathering with my friends generally involves something to do with a table of candles, and with telling stories about the year that has passed. Sometimes we talk about things we’re going to let go of; sometimes we do some light fortune telling. Then, just before midnight, we write our intention for the year on a slip of paper, and when the clock strikes 12 we light our intentions on fire, drop the ashes in our champagne, and drink them. (Sometimes we mix the ashes together in a bowl before distributing them into everyone’s champagne, just to make sure our futures are bound up together.)

Sitting in the dark around a table of candles is one kind of beginning, the kind that feels expansive and a little magical, the unknown all potential. The other kind of beginning is the sitting-in-front-of-a-blank-page-to-write kind, and that’s what usually greets me on January 1st, or second or third, when I’m scraping candle wax off my kitchen table in the cold slanty light of a January day. In this light, all my resolutions are beginning to look like illegible scribbles, and if, god forbid, I made any big plans I was going to start right away, well, fuck that. In this light, December 31st’s energy is starting to resemble Liza Minelli singing “Maybe This Time” — compelling, and unhinged, and we all know right away that it will absolutely, definitely not be this time.

I understand why this sours people on new years, why people deride the holiday as an opportunity to sell you the accessories for your unrealistic goals and deliver a sense of failure to your doorstep. Like my writing process, poor January has been chained to the god of perfectionism, that most short-sighted of gods, for too long.

I used to call this god discipline, or ambition, or high standards. I used to respect this god as the only one who was going to keep me from sucking, no matter how many times what he actually did was keep me from starting. After all, he does have a certain appeal, a certain buzzy, amphetamine-like pull. I do sometimes turn out a tight, slick piece of writing while under his thrall. The experience leaves me proud, and exhausted, and convinced this is what writing is: a high stress, high wire act, one I can only complete after days or weeks of anticipatory avoidance and build up.

Janus, the old Roman god for whom January is named, has two faces. He presides over doorways, transitions, beginnings and endings, and so I guess traditionally he has one face to look forward and one to look back. But I think the two faces could also serve as a reminder of beginning’s dual energies, both of which are useful in their own way.

We need the warm, expansive “maybe this year” energy of new years eve — this is the energy of imagining what we want without concern for logistics. (This is actually where the god of perfectionism belongs, where his cries of “Bigger! More! Imagine how good it could be!” are useful.) And we also need to be able to lower our standards enough to actually begin. The act of beginning is rarely elegant, or surefooted, or impressive. Why would it be? If beginning our year in winter has anything to teach, it’s a lesson about how beginnings don’t always look like beginnings, just like staring out the window doesn’t look like writing. It’s a lesson about action coming out of stillness, and conscious thought out of dreams. We are a month out from the darkest day of the year. The light is coming back, but it’s not here yet. We are still working in the dark.

Much of the scariness of writing is being with the unknown. You don’t know how it’s supposed to go. You don’t know what the shape is you’re moving toward. This is January energy. No showiness, no excess optimism. These might attract the attention of the perfectionist god, who will start to tell you that actually, yeah, this has real potential. If you just push a little harder, this could be great…Being great is not what January is for. This month, what is left of it, may we devote ourselves to doing things badly. To beginnings that are even more humble than you imagined they could be. To not being sure if you’ve even begun at all. This is the task. What happens after that is not yet our concern.