REVISION LIST:

Act two — weirder, go deeper

Kids performing middle age — lean into this

Act one, pacing?

Make Stella less white

Hmm. Where to begin.

Getting started on revising a play is always a little excruciating, like convincing yourself to swim in cold water. Is it really necessary? Should I just skip it? I know once I begin it will be worth it, but… shiver.

“Act one pacing” seems like the low-hanging fruit. Technical. Nice way to ease in. Maybe I’ll start there. On the other hand, the “kids performing middle age” thing is part of act two, so items one and two could actually be tackled together, which would put me halfway through my list right away…

But no. Let’s not fool ourselves. The first three items on the list are dip-your-toe-in revisions, revisions that are more about form than content. Tackling these first would be an avoidance tactic, a waste of time. So that leaves number four: make Stella less white.

Why, you ask, should Stella be less white?

And what is “less white,” anyway? Do you actually mean not white?

I’ll answer your first question first. This is a six character play, with four adults and two children. Stella is one of the two adults. I’ve already decided, for a constellation of reasons, that the other adult character should probably be white. Now, there’s nothing explicitly wrong with Stella also being white — that casting wouldn’t reinscribe problematic racial narratives or imply something major that I didn’t mean to imply. It’s just that the two adult characters are the ones we, the adult audience, most directly relate to. Their perspectives create the world of the play, and imply its parameters. This is not a play about race; it’s about friendship, and mental health and approaching middle age. Specifically, it’s about queer/trans people navigating these things — what does the stuckness or grayness or crisis of midlife look like for people who have taken less traditional life paths?

When I put this play in front of an audience for the first time in New York this summer, my audience was not particularly white. And I felt, in talking to several people afterward, that there’s something relatable in the piece to a wide swath of the queer and artist community, something not limited to white artists or white queers. (Maybe this seems like something I should have already known, but there are a lot of things you have to let go of tracking to let a play get written. So the first time hearing it with other people in the room usually involves a big recalibration — oh, that’s how it sounds in the world.) So let’s say this play’s primary audience is people in their 30s and 40s who relate to some sense of outsider-ness when it comes to traditional markers of family, career and success. One way to support that, and to hold the play open to the broadest group within that category, is to make sure the cast, and specifically the two anchor characters, are not all white.

Ok, you say, but it sounds like Stella is white. Isn’t that a little disingenuous to graft some other racial identity on top of the character in the interest of relatability, or marketability? Is this mercenary?

I’m not sure I would say a character is anything for sure when I start writing a play. I don’t always know a character’s gender or age or race, and I sometimes don’t know it for a long time. At the beginning, the characters are more like buckets of ideas, or pieces on a chessboard, than they are people. As the play takes shape this becomes less true — they gain dimension — but it’s still not uncommon for traits or even whole story arcs to get shuffled from one character to another a few drafts in. I think some writers start with a clearer sense of character, but I tend to start with themes and questions, and characters arise as they serve the themes and questions of the play.

With Stella, I understand her general position in the play: the other adult character, Sid, is undergoing massive change, while Stella’s life refuses to change. This is important. The two characters are coming at transformation from opposite sides. But what exactly it is in Stella’s life that feels stuck/unmoveable? This is less clear to me, and I’ve tried a few different options already. In this recent draft, the one I shared in New York, Stella developed a sort of obsession with the archetype of the housewife. Housewives appear elsewhere in the play, so I decided to explore this option in part becauseI thought it might have a nice resonance with this other section of the play. Of course not all housewives are white, but the idea of a housewife — the 1950s cartoon version — or in this case the 2024 cartoon version, a sort of upper-middle-class suburban chardonnay-drinking housewife — is. So if Stella is being played by a white woman, which in my New York reading she was, her intimacy with this archetype makes sense: it feels like a fate she narrowly escaped.

The housewife thing isn’t the only white-coded quality of Stella in the current draft, but for the sake of clarity, let’s limit ourselves to discussing this example, and look at our options. I could decide that this commentary on white suburban womanhood is actually a useful part of the play, and lean into it. In other words, I could decide to make Stella intentionally white, rather than accidentally white. This would probably involve fleshing out exactly why this archetype is such a demon for her. Maybe she feels like this archetype lives inside her, even though that’s not what she presents to the world. I don’t think I’ll choose this option, mainly because I don’t actually think this is what the play’s about. I didn’t set out to write a critique of suburbia, and the more I mentally map out this option, the more I feel that it pulls the play in unintended directions.

Which leads us back to making Stella less, or not, white. I could change what the character is obsessed with, choosing something that feels a little less coded in terms of race and class. Or I could change how the character relates to the housewife idea, making it clear that this is not a an archetype she fits simply or easily into. The former option would not require me to make a decision about Stella’s race; the latter probably would.

In the past, I have found a couple ways in to writing characters whose races are known and different than mine. One has been when investigating a particular racial dynamic — I’m thinking here about a piece dealing with gentrification in Oakland. The other way is when the character is at least a little inspired by someone I know in real life. Even if the character spins quickly into fiction, that small morsel of grounding in someone real has helped me not just avoid tropes, but also avoid obsessive worrying over what will or will not be perceived as a possible trope.

It might seem like making a specific choice about Stella’s race is the most responsible thing to do. After all, not doing so seems to reify the binary of white and “not white,” lumping all people of color into on undifferentiated category. But because neither of the above conditions are true — I’m not writing explicitly about race and I’m not writing about someone in my life — choosing a race for her feels a bit haphazard. So while it’s not a perfect solution, quieting the racial subtext of the character — making her less white — seems like the best solution to me right now.

Because I come from an ensemble theatre background, where I made a lot of work in collaboration, I’m always interested in whether working with an actor might shift or complete a character in ways I’ve not expected. Not all actors will want to do this labor or have these conversations, but some will. One possible outcome for Stella’s character is that the casting remains open/flexible with a preference for POC actors, and the character gets further shaped in conversation with the actor who gets cast. In other words, if a Latinx actor is cast as Stella, the character might become Latinx, and the casting requirements for subsequent productions might be changed to reflect this. I’m not talking about big script changes here; more likely it’s a few small tweaks, a moment here or there that gets improvised and added in. Of course, this is easier said than done. It requires developing a rehearsal-room culture where asking questions or offering opinions about racial subtext isn’t a high-stakes thing to do. It’s not something you can go into a process counting on, but I’ve experienced it as mutually satisfying a few times that it has happened.

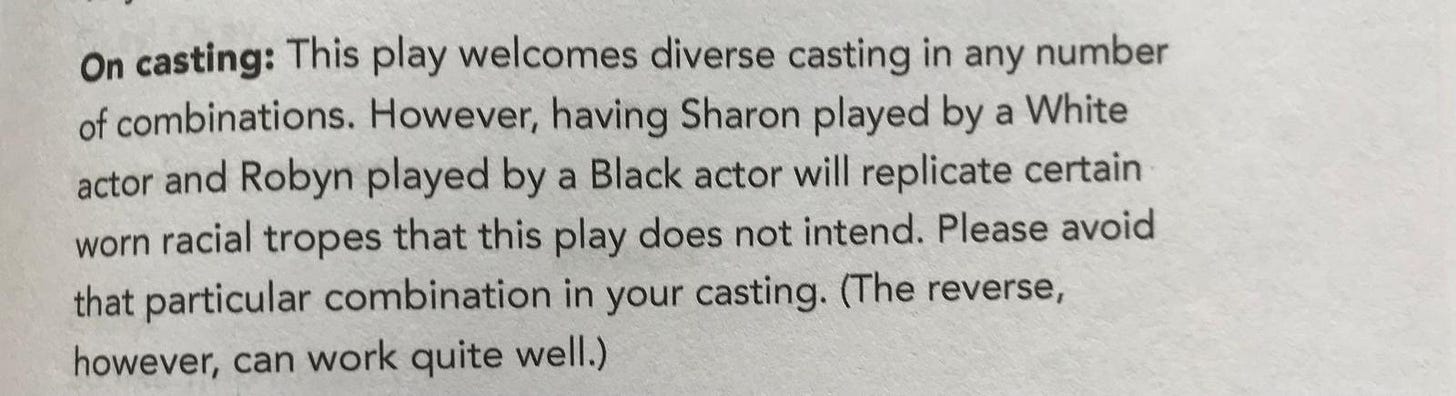

I bring this up to say: sometimes a script gets finished multiple times in multiple ways. The revision I’m doing now might not be the last time the script changes, so I try to relieve myself of needing to know everything about the character. Instead of thinking about whether or not I am writing Stella’s race, maybe a more accurate way to describe this revision is to say that I’m locating whiteness. I am mapping out where it currently exists in the play, and deciding whether that’s where I want it to be. This idea reminds me of some of Jen Silverman’s casting notes, which act as parameters inside which casting choices can be made:

From what I’ve encountered, this approach is unusual among white writers, and I see something useful —and honest — about it. It exists somewhere between the two poles we often get stuck at: on one end of the spectrum, not mentioning race at all, or on the other end, getting hyper specific in order to ensure multiracial casting even if the specificity is, ultimately, not deeply ingrained in the play. We need more attempts at language that exists between these poles, and I think in particular we need more practice locating whiteness within the work. Not locating it so we can eradicate it, but so we can work with it. And so we can think about what it means to actually write about whiteness in ways that go beyond performances of virtue or guilt.

* * *

I wonder if this all seems a bit granular, a bit obsessive, especially if you are reading this from somewhere outside the theatre industry. It can seem that way to me too sometimes, when I am sitting alone rearranging words on a page. And then actors step into your characters and zip them up, and your words are coming out of someone else’s mouth, and you remember that this act of transmutation is actually at the center of your craft. You write the outline not so it can stay an outline, but so someone can step into it. The characters you write become a rehearsal room of people, which becomes a set of collaborative relationships, a community. And so part of the instinct to “get it right” when writing race is to not re-inscribe society’s problems in this little community you are making.

Not that there is ever a getting it right. Better to begin with the knowledge that it’s an impossible task, me writing you. Anybody writing any other body. So why try? That sounds rhetorical, but it isn’t. I think it’s actually an important question to keep asking. Why try to write beyond myself, knowing I will, at least partially, fail? As long as the answer is real, and success has been dispensed with, then the impossible is a pretty interesting place to be.