The Shape of the Thing

Last month I saw a play in a language I don’t speak. This is not a new experience for me — I’ve seen plays in Russian, German, Italian — but it’s something I haven’t done in a while. It’s boring and fascinating at the same time. Boring for the obvious reasons, and fascinating because you remember how many shapes there are to a play beyond language. You’re in a wash of sound, grabbing onto the occasional word you know, and suddenly everything else — gesture, tone of voice, the brightness of the lights, the clustering and scattering of bodies on stage — is heightened in meaning. Suddenly any of these could be the story.

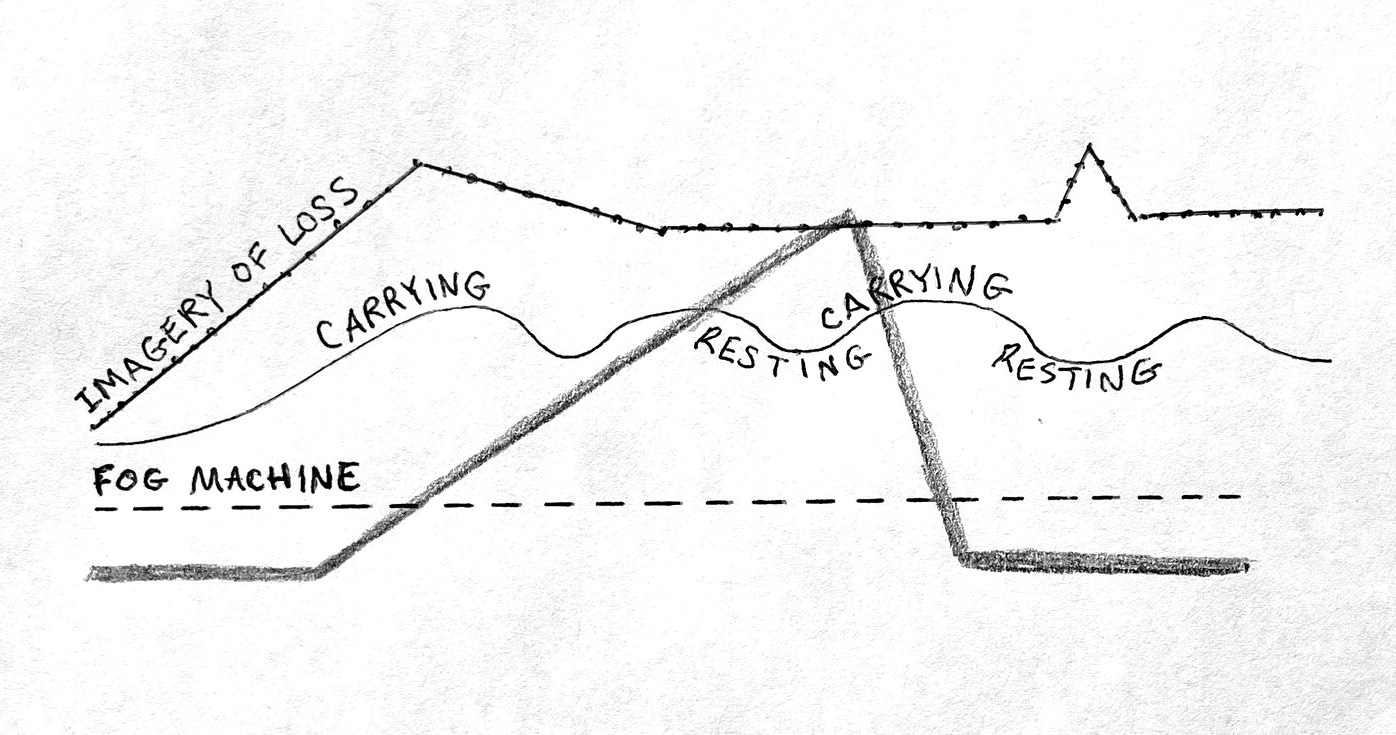

There was a sheep who got displaced from her homeland; someone died. I can’t tell you much more about the plot of the play than this. What I can tell you is that there were several gorgeous scenic gestures in the first half of the play that used empty clothes to symbolize absent people, and for a while these gestures built on each other, giving the feeling of accelerating loss. I can tell you that this visual progression peaked early, leaving me with a stretch of maybe 30 minutes in the second half of the play where I understood even less of what was happening because the same imagery was being repeated and remixed while slowly losing its impact. I can tell you that the other important objects of this world were baskets and bundles and fruits and occasionally pieces of paper. That one of the main actions of the story was carrying and resting and carrying some more. That repetition was used intentionally in the text and less intentionally in the movement. I can tell you a smoke machine ran the whole time, either to keep us from looking too hard at what was in the wings or to give the whole thing a fairytale quality, or both, and that my eyes were stinging from it by the time we left the theater.

It turns out language is only one layer of a play. As a writer, it’s the one I have the most control over, the only one that doesn’t involve a certain amount of translation as it passes through the hands of directors, designers, etc. But it is, actually, only a layer.

Language behaves differently in different plays. Sometimes it’s the skin, holding the thing in a shape, making sense — perhaps too much sense — of what’s inside. Sometimes it’s foundational: you get the feeling that everything else is issuing directly from the language, doing the language’s bidding. I can think of one play I made when I was with Ragged Wing that had maybe 5 minutes of dialogue in a 30 minute piece. Language was not the primary mode of storytelling, so moments of speech were like little eruptions, breaks in the surface of the landscape. When you write a script your only tool is language, but that doesn’t mean language must, by default, be the primary medium of the thing you are making.

It’s an interesting paradox, don’t you think? How writing a play is mapping something on paper that can be folded out into time and space. It makes me want to choose one of the metaphors above as a starting place. What is it to write a play thinking of language as a skin? What about writing a play where the language works in opposition to the shape of the action? These are exactly the kinds of play-making questions I get excited about. But I also admit to feeling, as I write this, a creeping sense of bitterness.

This bitterness has been ambushing me more and more lately when I sit to write, or talk about writing. It interrupts a promising lines of inquiry or interesting discussions of craft just as it is doing now. Excuse me, it says, but what exactly is the point of this?

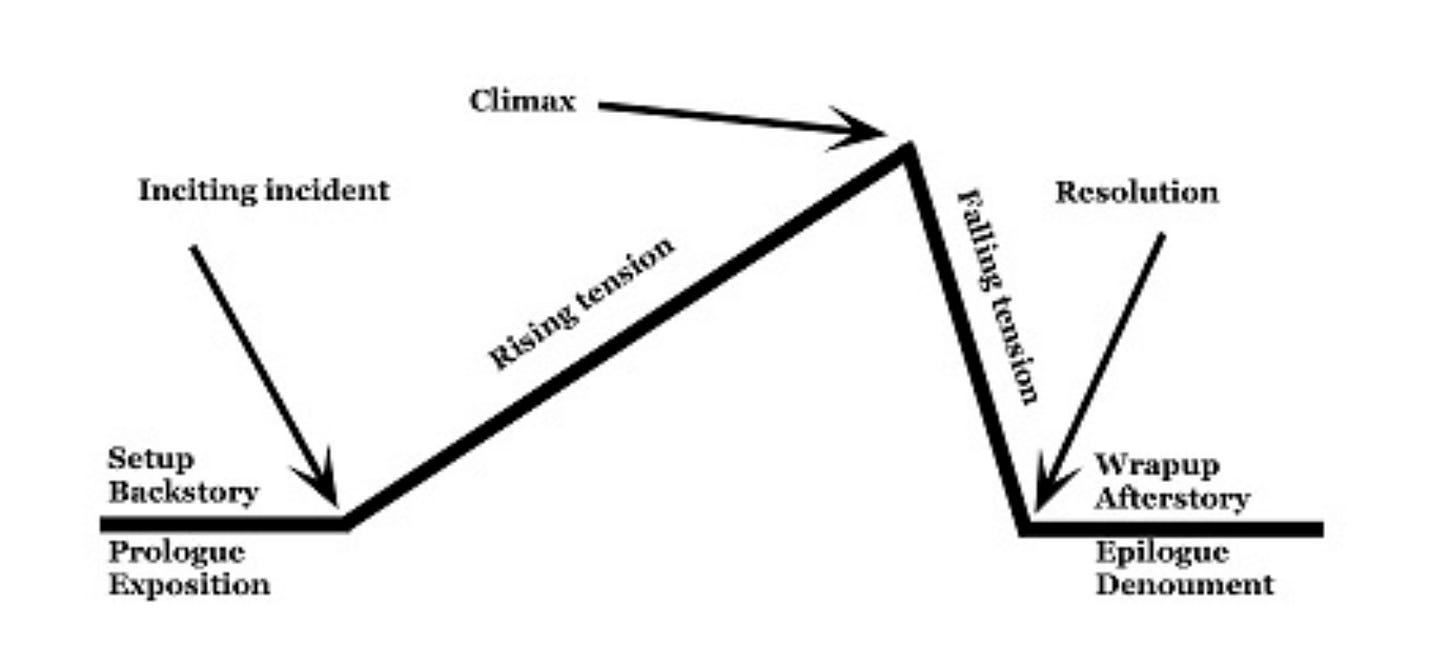

Because, despite various residencies, development opportunities, etc, the last couple years have been marked by a distinct lack of seeing my plays fully realized, in the flesh. They’ve gotten moments of attention — I’ve gotten to work with actors and a director for a few days here and there — but nothing has happened beyond that. Fog machines, dance routines, color schemes — all those things feel pretty far away these days. In truth, the spaces I am writing for are google drive and email attachments and notebook entries and databases that hold applications. The shape my plays make at the moment looks like this:

I know this isn’t unusual. I often look at the resumes of playwrights considered more successful than me who haven’t had a full production in years, or maybe ever. They’ve gotten more awards than I have, their scripts are given readings at bigger theaters, there is maybe even some money attached. But like me, it seems what they’re mostly making are scripts, not plays. We are making the blueprints, but the thing itself isn’t getting built.

I was spoiled by being part of a company when I first started writing. Everything I wrote got staged. What a gift, looking back. I had a lot of tumultuous feelings, in those days, about writing, but this bitterness was not one of them. I never labored over getting something just right only to put it in a folder and forget about it. It turns out doing that once is not so bad, but doing it a second time — when you are putting the new just-right thing you made into the folder next to the last just-right thing that is still sitting there, patiently waiting — is worse. By the third or fourth time, it is only sensible for some part of you to ask, what’s the point?

Yes, I know what you’re thinking.

(Well, maybe you’re thinking “can we end this detour and get back to discussing the function of language in a play?” If you’re thinking that then sorry, no, that ship has sailed.)

But if you’re thinking that I need to just make my own damn play, you’re right. I have to make a play myself. Not just the blueprint, not just the words, but the whole thing. I have known this for a while now. But I have been avoiding it because — well, how do I explain to someone not in the theatre just how awful self-producing sounds? There are a lifetime’s worth of things to get better at in writing plays. Like figuring out how to make language function like a skin. So to instead turn my attention towards doing the jobs of 10-12 other people, all jobs I’m not particularly experienced in or good at — fundraising, marketing, scheduling, hiring, securing a venue, ticketing, even directing and designing, depending on how shoestring my budget is — sounds to me like a lot of stress for a likely poor outcome. Not to mention the aggressive charisma required, the level of self-promotion and self-confidence involved in becoming a one-person make-it-happen machine. Just thinking about it makes me want to crawl under a large piece of furniture.

I think my objections are sound.

Still. It’s that or sit on my bitter pile of pdfs. So how to I make it bearable?

I’ve been getting a little inspiration lately, a little sense of possibility, from an unexpected source: my money job. I’m working at this recently-opened wine bar slash book store, run by two people pretty deeply embedded in Detroit’s small business scene. Detroit is a city where everyone has a side hustle, or three. Both to bring in business and to help out their friends, my bosses have been scheduling a steady stream of pop-ups of all kinds: every week there is someone in the corner of the bar selling their ceramics or hand-painted clothing or permanent jewelry. Fellow chefs and bartenders do kitchen takeovers, wheeling in crates full of sandwiches, ice chests full of oysters, or crock pots full of stews. Some guy who’s a musician and makes desserts on the side sold us a box full of creme brulees for serving on Valentine’s day. Some of these operations run smoother than others, some draw bigger or smaller crowds. Regardless, I’ve been surprised by the general level of patience and understanding people have for small businesses here. People show up to support the oyster guy. They don’t seem to mind that I have to ask for their credit card back three times because first he didn’t have a payment terminal set up and then his terminal wasn’t working and oh we didn’t have tips figured out for him but now we do. A little messiness seems to be accepted as part of running a small operation, rather than immediately labeled unprofessional.

In theatre we have a terrible fear of being labeled unprofessional, perhaps because so many people don’t have a clear idea what professional theater looks like. (If it’s not on Broadway or doesn’t cost a lot of money, isn’t it basically community theater?) As a result, I think we’ve developed a bit of an obsession with proving our professionalism, perhaps to the detriment of our cool factor. I’ve been thinking, as I watch the ice chests and crock pots wheel in and out: what might it be like to conduct my art making in this spirit? A little more, it’s not a big deal, I’m just going to pop up here, do a little theater, maybe people will like it. Nobody asks the oyster guy whether these are professional oysters. They just eat them.

It’s not that casual, of course: a play is not a one-woman operation. And I’m sure there is plenty of agony behind the scenes of even the smallest side-business. But from my vantage point, it looks like they’re finding a simple and direct way to do something they like to do. And customers show up, because they’re attracted to the energy of somebody doing a thing they’re good at. People are appreciative of someone taking the time to make a thing for us all to enjoy. There’s something in the spirit of that I want to hold onto, because it’s making the idea of making a play feel more spacious, more possible.

So that’s the shape of the thing. That’s what I am starting with as I sit down to begin this season’s project. Not questions about the function of language, or how to build an arc through the visual world of the play. Maybe — hopefully — I’ll get to those later, but for now I don’t get to start with things that seem like purer expressions of craft. The shape I’m starting with is this:

- something small. small enough to put in an ice chest. simple enough that you can pre-batch it in 16 oz delis and pack them in boxes in the trunk.

- something built for a space I have access to — not just a shabby version of something that wants to be in a theater, but something that belongs where it’s going to be.

- something that only requires a few people, people who will take what I can pay.

- something that feels, I think, a little too fun, a little too, “wait, really?” to be allowed. which is not to say there’s no seriousness in it; just that it when it’s very difficult, it doesn’t become drudgery.

These are the ingredients I’m starting with, and I’m going to see what shape I can make with them. This, too, is craft.

Usually, if a new thought derails what I set out to write about in one of these newsletters, I go back and reshape. I smooth things out and make sense of the trajectory. I haven’t done that this time. I really thought this was going to be all about the play featuring a sheep in the language I don’t speak, and the fact that it’s not leaves this essay messy and crooked. Well, so be it. That seems to be the lesson I’m learning these days: that what begins as an ill-advised detour becomes the thing itself, becomes the road you’re on, so best to just give yourself to it. Go forth and see plays in languages you don’t speak. You’ll be inspired. In the meantime, I’m going to attend to this bitterness, like the backdoor creme brulee dealer that I am.

Fantastic Addie. Love it and the idea.